A sense of safety and Indigenous connection: Joshua Wise on the meaning of home

Listen to the Story

Click here for audio transcript

Joshua Wise:

One of the craziest, I guess scariest memories I have from being in church, um, there was a traveling evangelist one time that came to our home church, and I think I was like maybe 12 years old, and I didn’t really care for church anyway, so I was like preoccupied with drawing a picture or something, and the minister snatched my sketch pad out of my hand, threw it on the ground and told me that I needed to pay attention to him because his was the voice of God.

And it really upset me because my dad was sitting right there and didn’t say anything. Just let it happen.

So that right there kind of like, solidified my disliking for any kind of organized religion, I guess.

My name is Joshua Wise. I’m a full time student at Tulsa Community College, umm I’m a stay at home dad right now.

I’m a member of the Cherokee tribe and I’m in the process of becoming a member of the Delaware tribe as well.

I grew up here in Tulsa, Oklahoma. Um I spent majority of it in northern Tulsa. But yeah, just true blue Tulsa, Oklahoman.

I would say, for sure, my grandmother definitely helped me, kind of form my own view, especially with the organized religion.

She definitely had a big influence on me researching my ancestry and kind of understanding the practices and culture and all of that.

If I described home in one word, it would be safe.

Probably because just growing up, I never had that sense of security or safety in the household. So to me, that’s what it means is just finding a place that is safe, that is home.

All growing up, my grandmother would take us to a lot of Indigenous events. That being powwows, or there were churches that did, um, this thing called a Green Onion Festival. And so every year you know they would, just put on this huge feast, and, you know, it was fry bread, really good food, and it was free to the community.

That was, that was one big thing that I learned from my grandmother is just the value of community and what that meant.

And so just being a part of that Indigenous culture and seeing how much is shared throughout everyone really, you know, opened my eyes and kind of gave me a different perspective of how I want to kind of pursue my life.

Some of my favorite childhood memories definitely involve Chandler Park. Um, a lot of the times we would come here with my grandmother

I’m taking kind of her, you know, note, and following suit. Like I take my kids, you know, hiking all the time.

I love the outdoors and I try and share that kind of culture with them because a lot of that indigenous heritage is, you know, the land that you live on. You’re self-sustaining. And so I try and give them that kind of quality of life.

My relationship with my grandmother was very close, to the point to where I consider her more of a mother than my own.

I remember before she passed I had this giant red mohawk and I went and saw her in the hospital and she just lit up.

She was so happy to see me and there was a big smile on her face and she said that again.

She was like, don’t ever change. She was like, I love that way that you are now.

So that, that just stuck with me and I’ve kind of let that resonate throughout my life and especially with my kids too, just being individual, you know. Don’t kind of go with the flow.

The idea of home to me, especially after having kids, is pretty much the same as when I was a kid. Um, I had mentioned before, I never really felt that safety. And so I’m very, um, focused on how my kids are feeling.

You know I’m always asking them how they’re doing. I’m sure it’s annoying, but I, I just want them to have that sense of, regardless of the situation, they can depend on me to be there or have that environment at home that there’s no judgment.

What is the meaning of

home?

Elena Johnson speaks with Joshua Wise, a Tulsa Community College student and dad. Growing up, he lacked emotional support in his household. His grandmother, Bonnie Louise Strickland, gave him a sense of safety with unconditional acceptance. By taking him on hikes and events like Indigenous pow-wows, he was able to feel like he had a community within his cultural identity, and learned about his ancestry. For Wise, home requires room for security without judgment, and his grandmother provided him with that.

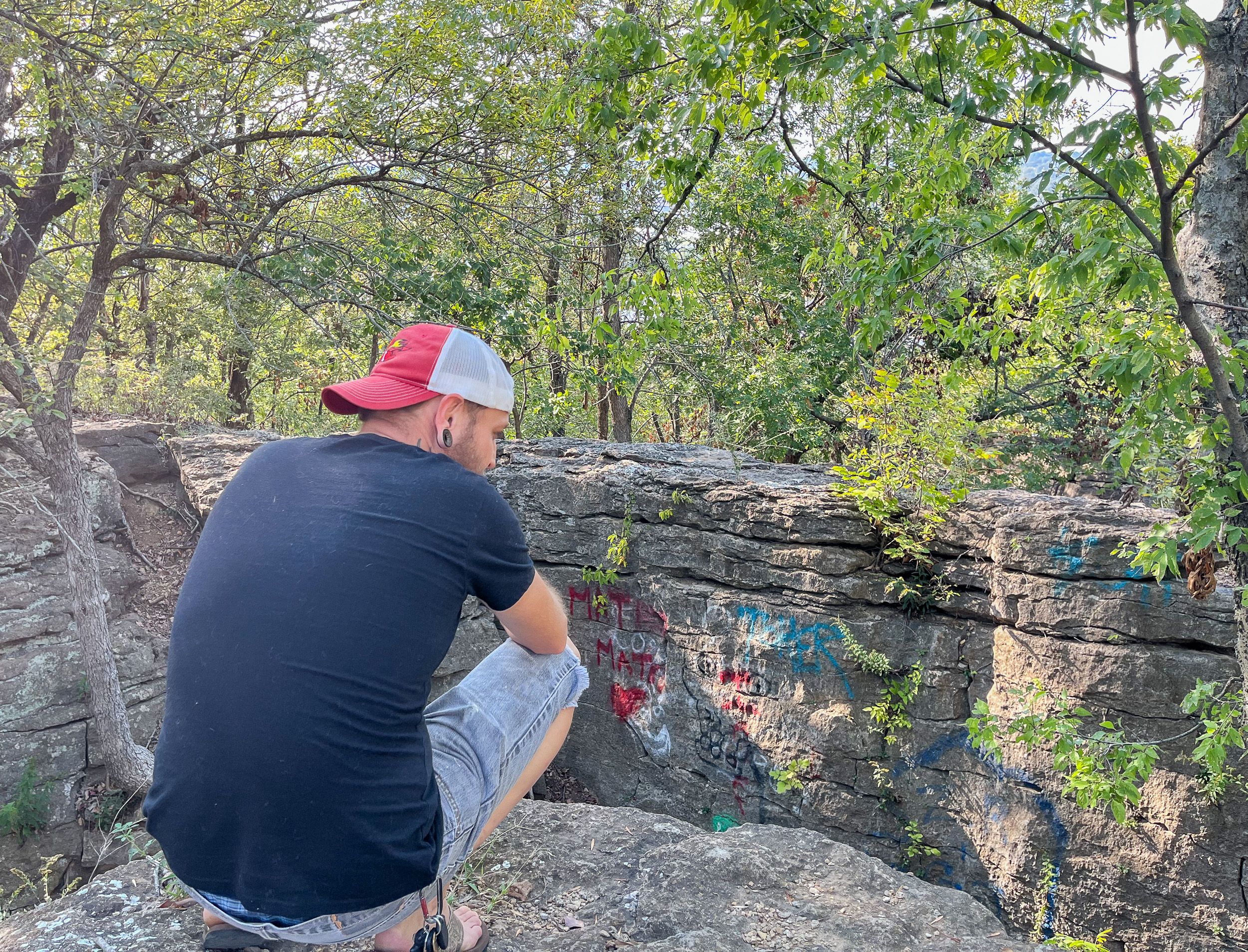

Some of Joshua Wise’s favorite childhood memories involve the caves and rock formations around Chandler Park in Tulsa, Okla. His grandmother, Bonnie Louise Strickland, used to take him hiking there as a kid, and he recalls the feeling of being young and having the freedom to climb around recklessly.

“Any time that I’m out in nature, it kind of reminds me of being out there with her,” says Wise. “It’s just a constant reminder of those good times.”

Wise, 41, is a stay-at-home dad and student at Tulsa Community College pursuing an associate’s degree in digital media. He grew up in Tulsa in a strict religious household and says he often felt alienated, with little freedom for self-expression.

“It was very, very scary as a kid growing up with that … just the sense of this imaginary person always watching you,” Wise says. “I was always in fear.”

Early on, the family attended a Southern Baptist church, but later moved to Free Will, a sect of Baptism, and a Charismatic church, a Christian denomination similar to Pentecostal. He remembers attending services with the threat of end times, and rituals like snake handling and speaking in tongues.

“I was, like, maybe 12 years old, and I didn’t really care for church anyway, so I was preoccupied with drawing a picture or something, and the minister snatched my sketch pad out of my hand, threw it on the ground, and told me that I needed to pay attention to him because his was the voice of God,” Wise explains. “And it really upset me because my dad was sitting right there and didn’t say anything. Just let it happen.”

In contrast, Wise’s grandmother provided him with acceptance and freedom for self-expression.

“My relationship with my grandmother was very close, to the point where I consider her more of a mother than my own,” Wise says. “She just nurtured me in a way that … I didn’t feel ashamed to be unique, or kind of go against the grain, especially with my religious family.”

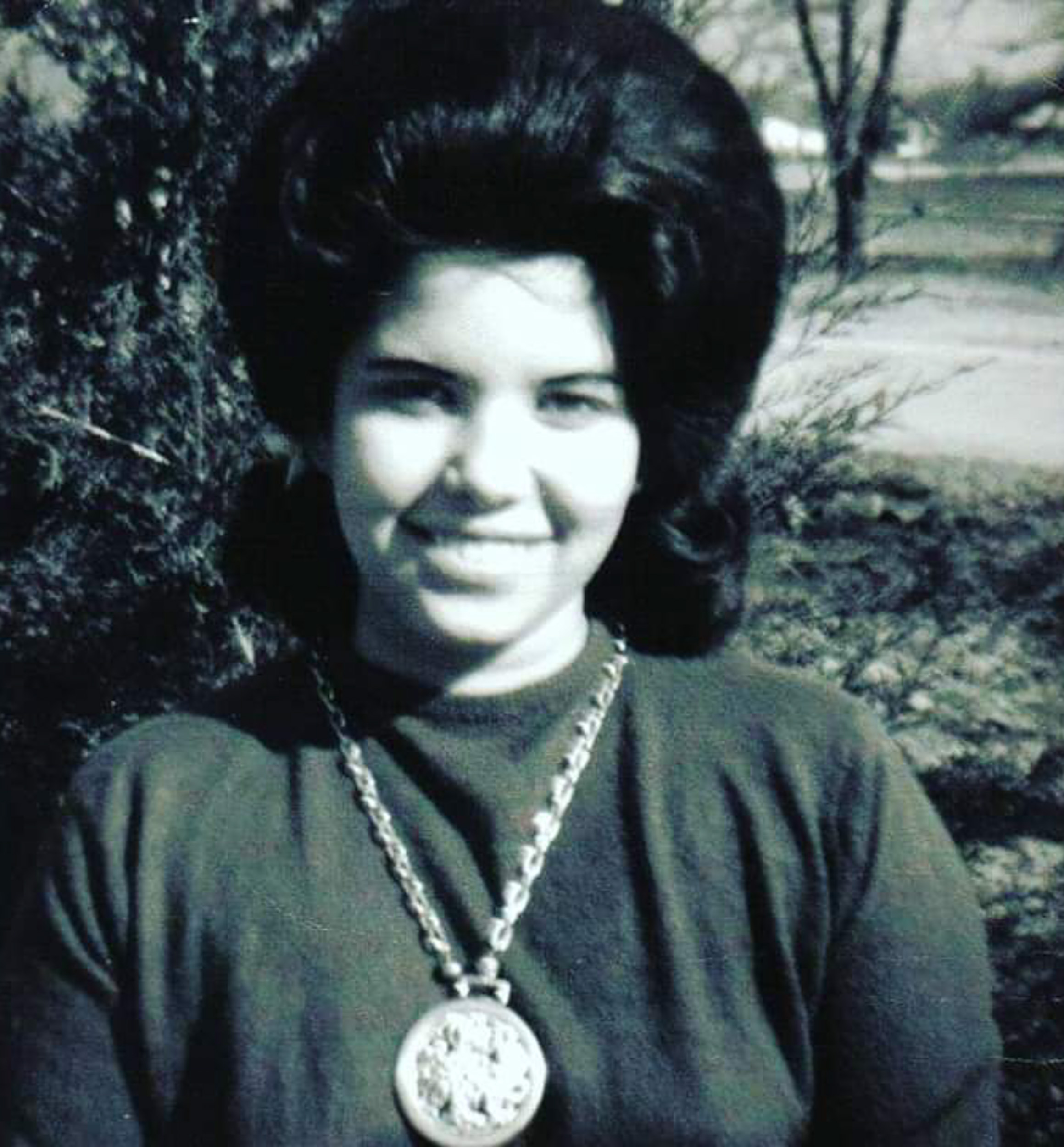

For him, spending time with his grandmother was an escape. Strickland was part Cherokee and made sure to nurture Wise’s Indigenous identity, educating him about his heritage.

“[She] definitely helped me form my own kind of view … especially with the organized religion,” Wise reflects. “It definitely had a big influence on me researching my ancestry and kind of understanding the practices and culture.”

Joshua Wise stands on a trail inside Chandler Park in Tulsa, Okla., on Monday, Oct. 2, 2023. “Some of my favorite childhood memories definitely involve Chandler Park. Any time that I’m out in nature, it kind of reminds me of being out there with her,” says Wise. ELENA JOHNSON / NEXTGENRADIO

EMILY WHANG / NEXTGENRADIO

“Having that kind of sense of knowing I come from a bigger picture and have a bigger family than just what was at home made me feel a little bit more safe.”

Strickland took him to Indigenous pow-wows and events like the Green Onion Festival, a large community dinner hosted by tribes throughout Oklahoma. He even started his own research into the Delaware tribe, also known as the Lenape, who originated in what is now Philadelphia and New Jersey, that was absorbed into the Cherokee tribe.

Connecting with this Indigenous culture gave him a sense of community that he felt he never had growing up.

“Having that kind of sense of knowing I come from a bigger picture and have a bigger family than just what was at home made me feel a little bit more safe.”

And for Wise, that’s exactly what home means.

“The idea of home to me, especially after having kids, is pretty much the same as when I was a kid,” he explains. “I never really felt that safety, and so I’m very focused on how my kids are feeling. I’m always asking them how they’re doing. I’m sure it’s annoying, but I just want them to have that sense of … regardless of the situation, they can depend on me to be there or have that environment at home that there’s no judgment.”

EMILY WHANG / NEXTGENRADIO

He recalls a story of when he visited his grandmother in the hospital before she passed away. He walked into the hospital room with a bright red mohawk, and her eyes lit up and she smiled.

“Don’t ever change,” she said. “I love the way that you are now.”

It’s his close relationship with his grandmother that influenced how he raises his kids.

“I take my kids hiking all the time. I love the outdoors, and I try and share that kind of culture with them because a lot of that Indigenous heritage is the land that you live on. You’re self-sustaining. And so I try and give them that kind of quality of life. It’s a little tricky because they are in a society that everything is kind of new and flashy. So it’s hard to pull them away from it and go camping, this day and age, but I do what I can. It’s challenging, but it’s also rewarding when you get to see them enjoy the outdoors like I did.”

Joshua Wise revisits the rock formations where he used to come with his grandmother as a child. “We would come here quite often just to kind of hike and explore with my grandmother. Anything to do with outdoors or nature, like camping, exploring, stuff like that was always a big part of my childhood,” says Wise. ELENA JOHNSON / NEXTGENRADIO

Joshua Wise’s grandmother, Bonnie Louise Strickland, photographed in 1960, was a major influence in his life. He credits her with helping him feel secure in his identity. “Having that kind of sense of knowing I come from a bigger picture and have a bigger family than just what was at home made me feel a little bit more safe,” Wise says.

PHOTO COURTESY OF JOSHUA WISE / NEXTGENRADIO

“I take my kids hiking all the time. I love the outdoors, and I try and share that kind of culture with them because a lot of that Indigenous heritage is the land that you live on. You’re self-sustaining. And so I try and give them that kind of quality of life.”

Joshua Wise has a tattoo of a sparrow on his neck dedicated to his late grandmother. Wise says she was more like a mother to him than a grandmother. “I chose to get sparrows because I remember hearing a story once that sailors would get a sparrow tattooed as a symbol for a fellow sailor who had died. So I guess it’s my way of remembering,” says Wise.

PHOTO COURTESY OF JOSHUA WISE / NEXTGENRADIO

EMILY WHANG / NEXTGENRADIO